AI and relentless execution

What history says about how young, unproven founders can win in the AI boom

Jan 5, 2025

We’re knee-deep in a modern gold rush. For the young and unproven builder thinking of starting a company, it’s easy to feel both anxious and jaded by the frothiness of today’s AI ecosystem. In just a couple years, startups have crowded every obvious AI application area (i.e. codegen, marketing, customer support). Each of these spaces has a couple clear favorites via the conventional markers of emerging success—massive funding rounds at insanely high valuations, star-studded teams, and strong revenue growth. It’s tempting to assume that these early market leaders will maintain their edge and live up to their hype as the next generational companies, leaving little room for new entrants to create value.

But those of us living out our first true tech wave should remember this hasn’t always been the case in the history of technology. Many of the iconic companies we know and love today were started by underdog founders years after their markets were already declared “won” by another player. We should expect the same to happen in this cycle. To better understand today’s AI boom and how underdog builders can create value, I wanted to take a look at some of these companies and identify what they have in common:

1. Internet search: Google vs. Yahoo

In 1994, Yahoo debuted on the once-fragmented Internet as “Jerry’s Guide to the World Wide Web,” quickly rising to dominate search engines for the rest of the decade and going public as a dot-com darling. Yet Yahoo and these early search engines were directory-based/curated and organized results by who paid the most, eroding the quality of their results by allowing advertisers to buy their way to the top. By contrast, Larry Page and Sergey Brin believed that what users truly cared about was the fastest and most accurate results. They started Google in the late 90s entirely focused on building a new search engine optimized around speed and relevance, and soon figured out a more unique business model that supported this core value proposition. Users loved it. By the time the mid 2000’s rolled around, it was Google that became synonymous to online search.

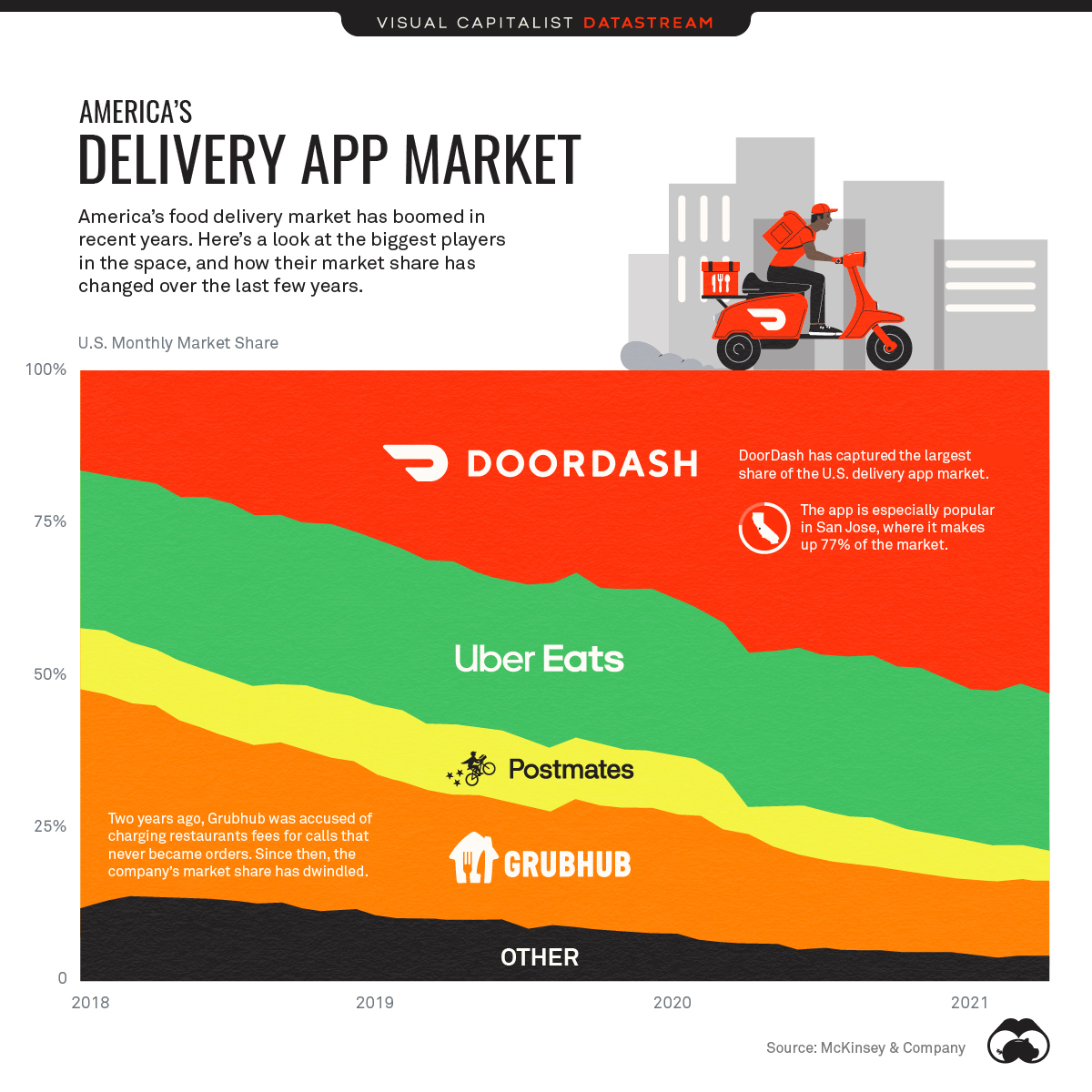

2. Food delivery: DoorDash vs. Grubhub/Postmates/UberEats

By the time DoorDash was raising its Series A in 2014, the online food delivery market had many major players: GrubHub had merged with Seamless and gone public, Postmates and Caviar were gaining meaningful traction, and Uber was just about to launch UberEats with the backing of their rideshare empire. When Tony Xu and Alfred Lin visited my class at Stanford last fall, Tony explained that DoorDash’s success hinged on a series of early, non-obvious bets—chief among them were starting with suburbs, not cities, and focusing on having the best selection of restaurants. Conventional wisdom was to start with cities, where deliveries were already happening naturally, but Tony was convinced that a service like Doordash’s would be even more valuable in lower-density suburbs where you had to drive a fair distance to get food and most restaurants didn’t offer any delivery. Through rigorous experimentation, they also discovered that people (especially in the suburbs) cared most about restaurant selection: adding a new restaurant on the platform most meaningfully increased consumer growth and engagement—more so than slashing prices or delivery times. So while competitors focused on cities and different axes of the service like delivery speeds and pricing, DoorDash went out to the suburbs and prioritized onboarding all the restaurants in the neighborhood. With the same kind of relentless hustle that led to these insights, Tony and his team were ultimately able to prove their strategy correct: as of March 2024, DoorDash has captured 64% of the U.S. food delivery market, with UberEats coming in a solid second at 23%.

3. Corporate card: Ramp vs. Brex

For decades, corporate cards have used points and rewards to incentive businesses to spend more, with American Express leading the legacy market by providing the best rewards program. In 2017, Brex entered the market as the premier tech-first disruptor. In a time when startups “literally couldn’t get a card,” they offered a quick and easy way to get a corporate card with 10x the credit limit of Amex and comparable perks. But in 2019, even as Brex reached unicorn status , Eric Glyman and Karim Atiyeh realized that incentives were still grossly misaligned—what companies really wanted was cost savings, not points or perks. That insight led them to found Ramp, introducing a corporate card without any rewards, simply 1.5% cash back and tech-enabled tools designed to save their businesses time and money. Ramp’s commitment to saving their customers time and money has proved immensely powerful: it broke records for the fastest-growing SaaS/fintech company in history by revenue, reaching $100 million in ARR within two years. In 2023, Ramp was estimated to have overtaken Brex in total payments volume (TPV), hitting $30B annualized and growing 209% YoY. Today Ramp’s secondary-market valuation stands at $11 billion, eclipsing Brex’s $4.1 billion.

Looking at each of these companies’ journeys side by side, we can identify one common thread crucial to their success: relentlessly resourceful and customer-centric founders. When Google, Doordash, and Ramp each got started, there was another startup at least a couple years ahead that was the clear “market leader” at the time. Overtaking them and creating the most enduring value in the market didn’t require some groundbreaking idea, the deepest pockets, or the biggest brand. The founders simply narrowed down on the right problem for their users and solved it relentlessly.

This is not to discount the merits of being a first mover or having a big war chest. These traditional competitive advantages have been important to many companies’ successes (e.g Uber outcompeting Lyft in ridesharing and Netflix/Amazon winning in video streaming). Some of the hottest AI startups today will create enduring value if they capitalize on their advantages properly. The purpose of this study is more so to shed light on the fact that it’s still too early to tell.

For the young and unproven, this is a heartwarming reminder to not be intimidated by the recent explosion of AI startups. Companies who are strong by consensus indicators shouldn’t deter you from entering the market or starting a company in the first place. If anything, seeing other players in your space of interest should be encouraging, since it’s a positive indicator of demand. You gain other advantages as a second mover: you can learn from others’ mistakes, won’t have to do as much market education, etc. The real question to ask yourself is whether you have the grit, determination, and willingness to make non-consensus bets.

In fact, compared to other periods of technological disruption, today’s AI environment is uniquely favorable for the relentless and resourceful. Rather than a distinct technological innovation like the invention of the PC or the launch of the App Store, foundation model capabilities and research paradigms are constantly evolving beneath our feet, creating a torrent of new product opportunities. For example, o1/o3 introduced a new shape of machine intelligence that unlocks use cases distinct from those of 4/4o—ones that require deeper reasoning, but perhaps aren’t as latency or cost-sensitive. Such a dynamic landscape also has a flipside: if companies who create some value today don’t move quickly to adopt and adjust to the latest innovations, they’ll quickly get left in the dust. The most value in the next couple decades will be captured by those who can hustle and iterate quickly.

Everything is still up for grabs. AI will change a lot of things in the world, but we can assume at least some of the fundamentals of building a generational company to remain the same. It’s just a matter of getting started—and executing relentlessly.